Each month two writers are asked to respond to a quote by Dr. Stanley. During June we’re considering the nature of grief and how we often want to isolate ourselves during that struggle. But in reality, those are moments when drawing near to others becomes critical. Here’s an excerpt from Dr. Stanley’s book Emotions, with responses from Jamie A. Hughes and Tim Rhodes.

“A person who struggles with rejection often experiences difficulty in establishing genuine give-and-take friendships with others and may feel as if no one truly wants or understands her. To avoid the pain of feeling unwelcome, she may either intentionally or unconsciously separate herself from others. …Such isolation eventually causes the individual even deeper loneliness and bondage.

“If you struggle with loneliness and rejection, you may face a temptation to camouflage your sadness from others and distance yourself further. Don’t do it.”

“Conversely, a person who spends a great deal of time alone—and thereby does not have opportunities to practice interacting with others—may be misunderstood as aloof, awkward, or detached in social situations, which then elicits undesirable and adverse reactions from her peers. When such negative interactions occur, feelings of inadequacy and rejection can develop and more wounding can occur.…

“If you struggle with loneliness and rejection, you may face an overwhelming temptation to camouflage your sadness and disconnectedness from others and distance yourself from them further. Don’t do it. No Christian has ever been called to “go it alone” in his or her walk of faith. The Father created you for relationship and calls you to live in meaningful fellowship with other believers (Heb. 10:24-25). Therefore, acknowledge your loneliness to God and trust Him to help you overcome it.”

Take 1

by Jamie A. Hughes

Funerals are strange affairs.

I remember thinking this on the day of my grandfather’s memorial service. We were all heartbroken, and the last thing we wanted to do was get dressed up just to spend the afternoon talking with people and eating lukewarm food on plastic plates. But that’s precisely what we did. After I got myself ready, I spent most of the morning putting my niece’s long brown hair in hot rollers and helping her get into a pretty pink dress specially bought for the occasion. I didn’t have time to grieve or to be lonely because there was simply too much to do.

The loneliness didn’t surface during the service when I gave the eulogy or once the meal was over. It was after we’d gotten back to the house that it hit me. Some members of my family, exhausted and drained, went upstairs to take naps. Others went to busy themselves in one way or another. But I had nowhere to be and nothing to do, so I kicked off my pumps, sat down in one of the living room’s wingback chairs, and stared at the cold, empty fireplace.

Busyness had allowed me to sideline my grief, but once all the work was done, the full weight of my loss made itself known. I couldn’t get up and do something to distract myself. Even taking a deep breath in that moment felt like too much of an effort. There were seven or eight people in that house, as evidenced by the creaking floorboards and bedsprings above my head and the muted conversation in the kitchen, but I felt so alone in that moment. There was no one near me, no one to whom I could speak. Not really. That was when I felt loneliness the most keenly.

After a while I couldn’t take the silence any longer, so I decided to change clothes and go for a walk around the neighborhood where my grandparents had lived happily for nearly 30 years. It’s a quiet subdivision, no more than four or five well-maintained streets, and I took my time traveling each one of them. Why not? The day was warm, and the sun felt pleasant on my shoulders. I saw a few neighbors out mowing their lawns and trimming bushes, and the breathtaking normalcy of it all struck me. This day—one of the worst of my life—was someone else’s random Friday. Maybe the couples I saw were going on a date that night. Maybe the grandkids were coming over for dinner. There were things to look forward to, things to enjoy in their life, and I suddenly realized that one day it would be that way again for me, too.

I didn’t have time to grieve or to be lonely because there was simply too much to do.

I realized my grief—isolating and painful as it was that day—would one day fade to a dull ache, and that gave me comfort. I knew those people working in their yards had had days like the one I was enduring, had known pain like the kind I was feeling, and they’d gotten through it in time. That made my loneliness feel less acute somehow, and I finished my walk heartened by the knowledge that, as a human being loved by God, I was never truly alone.

Take 2

by Tim Rhodes

I scrutinized myself in the mirror one last time before opening my laptop. I was wearing a tie and blazer for the first time since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic—easily nine months since the cancellation of any and every formal, in-person engagement. I had already forgotten how to tie a half-windsor, the easiest of knots.

I started Zoom on my computer, took a deep breath, and entered the code to my father’s memorial service. In one of the many rectangles on our screen, I saw a view from his rooftop garden in Mérida, Mexico. Next to vine-covered walls and tropical foliage sat a table with flowers, candles, and a statue of the Virgin Mary. A framed photograph of my father rested in the middle of the hallowed arrangement.

I started Zoom on my computer, took a deep breath, and entered the code to my father’s memorial service.

At the same time I was inundated with dozens of random faces I’d never seen before. Aside from my siblings, there was only one other familiar person in the group. As I watched people with unknown names and voices greet each other and talk back and forth over one another, it felt as if salt was being poured over an already extremely raw and personal wound. Many on the Zoom call were friends Dad had made after moving to another country five years ago—people my father valued and chose to include in his life.

Their simple and innocent act of recognition and excitement to see one another took me by surprise. All the pleasant memories these individuals shared about my father were ones my siblings and I had never experienced ourselves, the descriptions of warmth and loyalty unrecognizable. Although the recollections were meaningful, they also amplified the feelings of isolation we felt as his children. As his flesh and blood, we were observing the commemoration of a person we did not recognize. Someone who never invited us into his life. We weren’t separated from him solely by the pandemic and the Gulf of Mexico but by a lifetime of choices—clear determinations of what my father held dear.

And now we were separated by more. Whatever rift was felt in life cannot match the abyss felt in death—the intense loneliness of knowing there was never a turning point, never a critical moment where he recognized and reciprocated the love and longing and need for him in our lives. It’s a closed book, a final act. While there’s no way to remove the pain, there is a way to start to heal—by processing with my siblings and helping them work through their own feelings of rejection. By cherishing every moment with my own children and ensuring that there will never be a day or hour or second that they will question my love for them.

First John 3 reminds us, “See how great a love the Father has given us, that we would be called children of God” (1 John 3:1). The Father of heaven and earth, the creator of the universe, not only knows us intimately but also wants to.

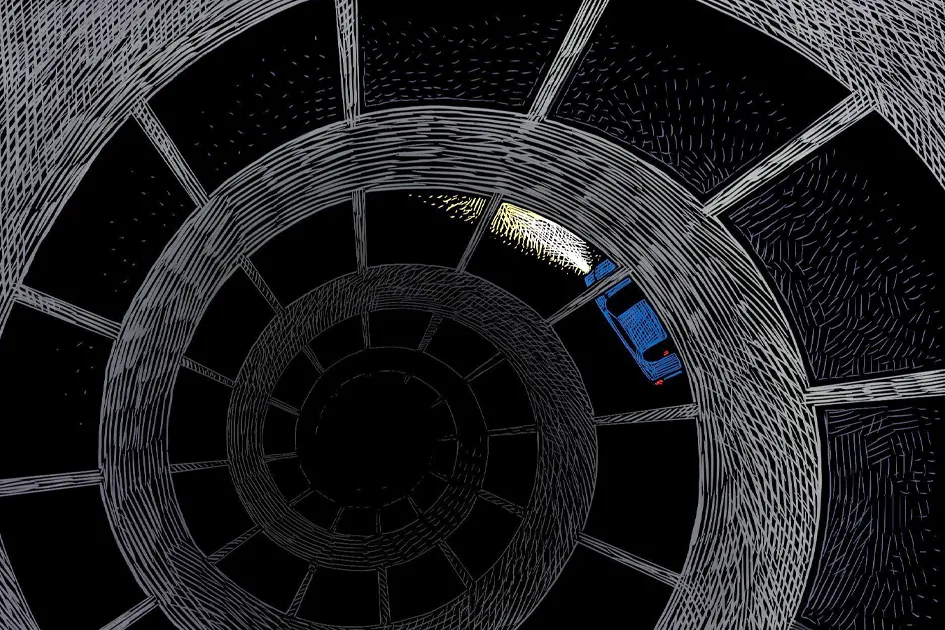

Illustration by Adam Cruft